California’s first licensed female architect and one of the first female graduates from Beaux-Arts in Paris, Julia Morgan is best known as the designer of the elaborate and expensive Hearst Castle in San Simeon, California. Lesser known is her more prolific work for a client very different from William Randolph Hearst; and perhaps she should be better known as Julia Morgan, designer of lodgings and meeting houses for the Young Women’s Christian Association, the YWCA.

In the latter half of the 19th century and into the early 20th, the YWCA played an important role in the female social sphere. For rich and middle class women, it offered an area of expanded social influence outside of the home–an outlet for business-minded women to help reshape society. For the less-than-rich, the YWCA was a haven. Its stated goal was “to advance the physical, social, intellectual, moral, and spiritual interests of young women” (quoted in Mjagkij and Spratt, 272). To these ends, local YWCA chapters tended to offer opportunities like Bible studies, recreational activities, vocational classes, employment help, and lodging.

This was especially important at a time when many young women from rural areas were migrating to the cities for better working opportunities. In some ways, the YWCAs made this migration possible, or at least made it safer and more convenient, providing these women, especially those who may not have had families or friends in the city, with safe, comfortable, and respectable spaces to live more or less independently, but within a dominantly female social sphere.

In California, somewhere around thirty of these lodging and chapter houses were designed and built by Julia Morgan. Julia came from a middle-class family from Oakland. She was a warm-hearted, industrious, if reserved person. She struck out on an independent path for herself early in life, studying civil engineering in Berkeley and architecture in Paris, where she hung around until the Ecole de Beaux Arts decided to let women officially graduate; and yet she spent the rest of her life contentedly with or nearby her family, never marrying, reveling in her work, having her employees over for Thanksgiving, and buying individualized gifts for their children at Christmas. In fact, after designing so many buildings for the YWCA, she turned down their offer to become their national chief architect, because she did not want to leave her family and architectural compatriots in California. She upheld the highest standards for her designs, and believed no work was unimportant. “Don’t ever turn down work,” she once told one of her proteges. “[O]ne of the smallest jobs I ever had was a little two room residence in Monterey. . .and now the lady is the chairman of the board of the YWCA. And from that has come all these fine big jobs we have.” (quoted in Cary, 59).

The “lady” was Julia’s old school chum, Grace Merriam Fisher, director of the Oakland chapter of the YWCA. The Oakland YWCA chapter house was one of the first YWCA buildings Julia would design. It was built in a simple but dignified classical style, designed to let in as much natural sunlight as possible and deflect much of the noise from the busy street outside, to make a space that was both beautiful and tranquil–a haven for the busy working women coming in from the outside world. Julia personally sat on the floor and sorted through thousands of individual tiles called for by the decorative design, throwing out any that didn’t meet her standards.

Through another friend, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, whom she had met in Paris and who had encouraged her in her early studies and career by offering her some of her first commissions, Julia was also commissioned to build the YWCA a retreat center on the coast. Dubbed Asilomar, it is still in use today.

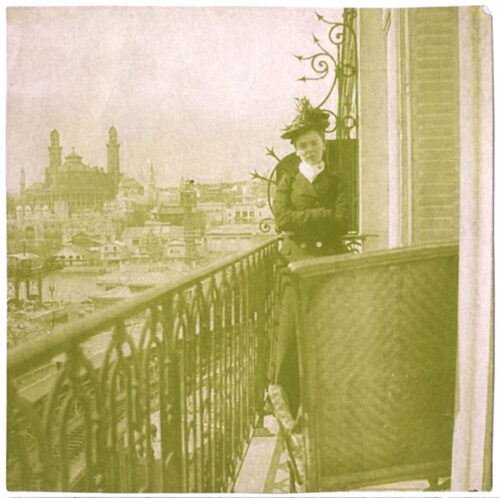

Among the other notable YWCA facilities Julia designed was the Chinatown YWCA in San Francisco, and a YWCA lodging house for Japanese American women. In both of these, Julia was careful to incorporate design elements from the cultural heritage of the prospective occupants. One of the last facilities she designed was the YWCA chapter house in Honolulu, the only one for which she could not personally oversee the building.

Nor was the YWCA the only women’s association that Julia designed for: women’s meeting halls, hospitals for women with tuberculosis, and buildings for Mills College, originally a women’s college, stand among her other significant work. In many cases, her services were donated. Her social network and career were largely a network of strong and vital female connections. (Even her most prominent work, undertaken for William Randolph Hearst, only came about as an offshoot of her working relationship with his mother.)

In all of Julia’s YWCA designs, the one element she emphasized was the human dignity of those who would be using the space. Once, when she was meeting with some YWCA officials about a residence house she was designing, “she said, ‘I found that we have a little extra space here. . .My idea is to have one or two little private dining rooms with little kitchenettes so that the girls can invite their friends, and cook a little meal and have a little private dining room,’” Hettie Marcus, a YWCA board member, recalled. “Well, a lot of the board opposed it. They said, ‘These are minimum wage girls there. Why spoil them?’ And she said, ‘That’s just the reason. That’s just the reason.’ . . .The next time we were together she [had] planned these rooms” (quoted in James, 91-2).

Morgan [always] kept in mind the human needs of the people who would use her buildings.

-Cary James, author of “Julia Morgan: Architect”

Philosopher Edith Stein, a contemporary of Julia Morgan, once said that the benefit of having women in spheres that were traditionally dominated by men was that the women were less likely to let the human element be forgotten amidst the numbers and theories of the work. That is one tenet that Julia Morgan, at least, certainly proved right.

For more information on Julia’s designs, check out this website, which maps her work in the Bay Area.

Sources

James, Cary. Julia Morgan: Architect. Chelsea House Publishers: Philadelphia, 1990.

Mjagkij, Nina, and Margaret Spratt (editors). Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and the YWCA in the City. New York University Press: New York, 1997.

Stein, Edith. Essays on Woman. (2nd ed.) Trans. Freda Mary Oben. ICS Publications, 1987.

- Not a Place Where No One is Watching: The Courage of Noor Inayat Khan, Pacifist and War Hero

- Dignity of Shelter: Julia Morgan and the YWCA

- Marcia Lucas: Film and Heart

- “All the World is Waiting for You”: Wonder Woman and the Feminine Genius of Edith Stein

Leave a comment