“[T]he hare lay in the grass in the woods, and his beautiful eyes were moist with sadness. ‘What can I offer if any poor creature should pass by the way?’ he thought. ‘I cannot offer grass, and I have neither rice nor nuts to give.’ But suddenly he leaped with joy. ‘If someone comes this way,’ he thought, ‘I will give him myself to eat.’

-Noon Inayat Khan, Twenty Jataka Tales

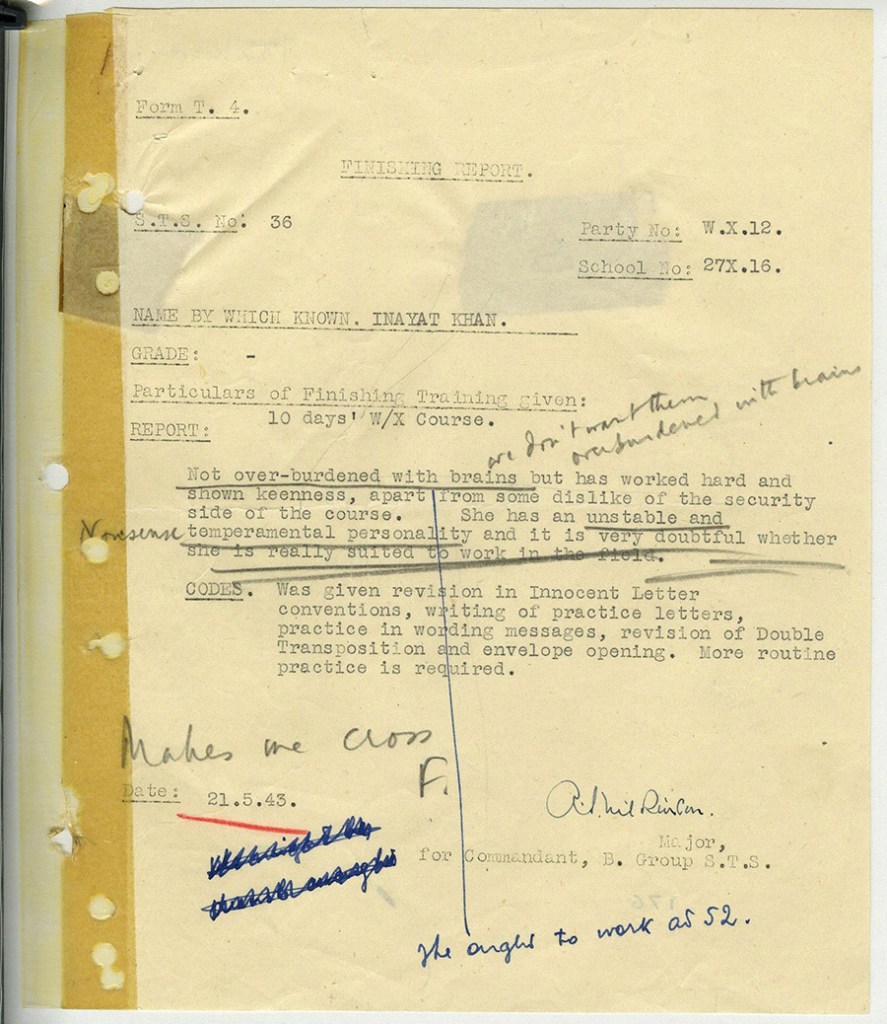

Those in charge at the British Special Operations Executive had their doubts about Noor Inayat Khan. Her training records are littered with concern that she wouldn’t be able to do her job. She was shy, naive, gentle, imaginative, emotional. She’d studied child psychology and music; before the war she wrote and illustrated children’s books. When she was given her ‘fake-Gestapo-raid-in-the-middle-of-the-night’ test, she reacted so poorly that her superiors found it “almost unbearable” (quoted in Helm, 136-37). “[S]he confesses that she would not like to have to do anything ‘two faced’” one report noted. Some worried that her physical appearance, her Indian heritage, meant she was too distinctive and would not be able to blend into the background. There was also the little problem of her distaste of her security training. In fact, Noor was a pacifist.

Raised by her Sufi father and American mother between Russia, England, and France, Noor possessed a deeply spiritual character and an admiration for the teachings of Mahatma Ghandi. She did not lie. She could not see how violence could solve the problem of violence. But she also could not look on and do nothing while violence was being committed around her as the Nazis advanced across Europe. What could she do? She discussed it with her brother, and together they came to a solution: while they would not commit violence, they would be willing to throw themselves in its path in order to stop it. They would take “the most dangerous positions, which would mean no killing” (quoted in Helm, 16). And Noor had a skill coveted among the British ranks–she was trained in how to operate a wireless. So, she became a spy.

Vera Atkins, the head of SOE, met with Noor before she was deployed as the first Allied radio operator to be placed behind enemy lines. She wanted to offer Noor a chance to back out. But Noor refused. So, with many misgivings, she was sent to France. Her unit was almost immediately captured, but when word came to the British that Noor had not yet been rounded up, she was informed she would be picked up immediately and brought back to England. There was just one problem. Noor knew that the other radio operators were among those already caught. If she left, there would be no one left in Paris to send communications.

So, Noor–gentle, kindhearted, “emotionally unstable,” whose superiors considered her too fragile to withstand the war–refused to leave. When she was eventually captured and the Gestapo tried to get her to send false signals, she gave them nothing. She died in a summary execution at Dachau, because she refused to cease her escape attempts, one of which she coordinated with other prisoners by tapping Morse code on the prison walls. Her last word was “Liberte.”

There is a tendency, for a woman to be admired, to require her to be strong, in the way many men would stereotypically define strength. She must not show weakness, she must not be too emotional, she must not be shy or timid or do things like tell stories to children. There is value and heroism in the other way of defining strength too–self-control is a virtue, for instance, and confidence a handy thing to have. But Noor’s life posits that perhaps that is not the only, the necessary, kind of strength. I overheard a mother the other day talking to a little boy who was afraid of something. If you were not afraid, she said, it wasn’t being brave, only daring. To be scared and do it anyways, that was courage. And courage isn’t defined by displaying stoicism, or confidence, or being too busy with the big things in the world to bother with the littlest people in it. Maybe courage is something that sometimes springs from gentleness. Maybe a kind heart is what makes it bearable to stay in the dark. Maybe knowing what it is to be scared makes a person more willing to reach out to others through the prison walls.

In one of her many stories for children, Noor told of a monkey whose back was broken when he made himself a bridge for people to cross over in order to escape danger. When a king comes across him and questions the reason behind it, the monkey assures him, “I do not suffer in leaving this world, for I have gained my [people’s] freedom. And if my death may be a lesson to you, then I am more than happy. It is not your sword which makes you a king; it is love alone. Forget not that your life is but little to give if in giving you secure the happiness of your people” (Khan, 21). And so, Noor said “Liberte.”

“[F]ull of joy the hare jumped into the glowing fire. But the flames were cool as water, and did not burn his skin. . .”Dear one,” [said the fairy]”. . .This fire is not real, it is only a test. The kindness of your heart. . .shall be known throughout the world for ages to come.”

-Noor Inayat Khan, Twenty Jataka Tales

Sources

Atwood, Kathryn. Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago Review Press, 2011.

Helm, Sarah. A Life in Secrets: Vera Atkins and the Missing Agents of WWII. New York: Anchor Books, 2005. ISBN 978-1-4000-3140-5.

Khan, Noor Inayat. Twenty Jataka Tales. Inner Traditions International. Rochester, Vermont, 1991.

National Archives. Who was Noor Khan? Nationalarchives.gov. Accessed August 21, 2024.

- Not a Place Where No One is Watching: The Courage of Noor Inayat Khan, Pacifist and War Hero

- Dignity of Shelter: Julia Morgan and the YWCA

- Marcia Lucas: Film and Heart

- “All the World is Waiting for You”: Wonder Woman and the Feminine Genius of Edith Stein

Leave a comment